The Mathematics of Change

Amanda Kabak

The Hellum & Neal Series in LGBTQIA+ Literature • Release Date: June 6, 2017

Print ISBN: 978-1-942083-46-7 • Ebook ISBN: 978-1-942083-49-8

Brain Mill Press offers The Mathematics of Change in ebook and in a limited fine first edition printing of signed, numbered paperbacks. Ebook buyers receive access to MOBI (Kindle), EPUB, and PDF files, offered without DRM restrictions. Print book buyers receive a physical copy of the book and access to the ebook files in all formats.

"Amanda Kabak is a writer to watch. She's an old-fashioned storyteller whose sharp eye is trained on a changing world. Smart, funny, and heartfelt, The Mathematics of Change is a brilliant debut.”

—Tayari Jones, author of Silver Sparrow and an Oprah's Book Club Pick for An American Marriage

The Mathematics of Change breaks open and breaks down the equation of midlife, proving balance is imaginary and change the only possible solution.

The aching and terrible excitement of Carol’s affair with her graduate school professor has settled, fifteen years later, into the frustrated complacency of faculty wife responsibilities and motherhood.

Carol wants more, but can’t have more.

She can’t have as much, surely, as her best friend, the painfully enigmatic Mitch, who keeps their long-ago erotic relationship irritatingly compartmentalized and spends too much time in her secret lair of an engineering lab.

She can’t have what the gorgeous new faculty member Abby has — a publishing career, slinky dresses, and a way of prying out vulnerable and damaging confessions from even causal acquaintances.

Mitch knows Carol wants more, but she also knows it can’t come from her. She’s grappling with the terror that comes from knowing she could have everything. Her lab is on the verge of a breakthrough, and then there’s Reginald: warm, funny, British, impossibly long-distance, compelling. Except, she’s not really talking to Reginald, unless she can’t help it. Meanwhile, Carol is talking to her too much and desperately yanking their past out of the mothballs, and Abby’s primary scholarship seems to be predatory and tempting advances.

Mitch could have more than she ever thought possible, but she can’t work out the math.

A darkly witty debut novel from the recipient of the 2017 Al-Simāk Award for Fiction from Arcturus and The Chicago Review of Books.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amanda Kabak is the author of The Mathematics of Change, a novel. Her recent work has appeared in the Massachusetts Review, Tahoma Literary Review, Sequestrum, and the Laurel Review, among other publications. She was a recipient of the Al-Simāk Award for Fiction from Arcturus Review, the Betty Gabehart Prize from the Kentucky Women Writer’s Conference, and the Lascaux Review Award for Fiction.

AN EXCERPT from The Mathematics of Change by Amanda Kabak

© Amanda Kabak, 2017. All rights reserved.

Chapter 3

“Freedom from the need to prove herself as capable leads to the possibility of discovering a true sense of self.”

—Dr. Abigail Rosen, The F Word: Femininity in the New Century

Womanhood found Evelyn Mitchell in her bedroom on a Saturday deep in her thirteenth year. It met her on a rare morning when she wasn’t at a swim meet, practice, or clinic, and it manifested itself as an ache in her back that made her think of endless laps of breaststroke. Coach Smith, with her loud whistle and greenish cast to her blond hair, told her the stroke wouldn’t strain her muscles if she did it right, but Evelyn couldn’t wrap her body around those froggy motions.

No matter how much she stretched and turned over, a sweet morning dream was elusive, so Evelyn shuffled down the carpeted hall with sweatpants heavy on her bony hips and one hand pressed against a kidney, trying to erase the ache. She could hear her mother downstairs in the kitchen and smelled the sharp saltiness of frying ham. The bathroom Evelyn used was up the hall from her bedroom and hosed down in powder-blue tile, but its hideousness was balanced by the fact that it was hers, alone. A year ago, she’d worked her mechanical genius on the lock, and now it couldn’t be picked, jimmied, or forced by anyone—most especially her mother. Evelyn could wile away the time in the bathtub with the flat tables of her kneecaps poking through hazed water, reading a book or magazine until she was chilled through. Even when her mother knocked on the door every ten minutes to check on her, her solitude was guaranteed.

This morning, after putting two and two together and arriving at a dreaded four, Evelyn sat on the toilet for a long time. There had been a lot of locker room discussion about who had it and who didn’t, “it” taking on varied meanings as she got older. Hair down there and breasts and menstruation were tallied and measured to enough significant digits a statistician would be proud. They traded horror stories of excruciating cramps and blood-spot embarrassment, rules about white pants and bra straps.

The whole thing made Evelyn nervous. Obviously, all the girls on her team and at school had no doubts she was one of them. With some, she’d horsed around naked since before they had their permanent teeth. The boys, though, were a different story. They knew she was a girl in a manner only half realized, and Evelyn wanted to keep it that easy way. If she suddenly sprouted breasts, there would be no way to navigate among them undetected.

Besides, there was her father, who had taken a giant step back from Evelyn as soon as her twelfth birthday had rolled along. He became distant, closed the door behind him when he went into his den, declared that she was becoming too advanced for his home-grown math problems. He’d become only a sharp eye on her grades and a back always receding down a hallway. Evelyn had tried in vain to determine how he’d calculated age twelve as the end of her girlhood, a question her mother answered with, “You’re growing up.”

“But I was growing up last year, too,” Evelyn said.

“Smarty pants. You know what I mean. Who do you think knows more about becoming a woman, your father or me?”

“Yeah, but . . .” Evelyn said before remembering that phrase held the status of a four-letter word with her mother.

“When you get older, things change.”

“But I like things now.”

“And why not? When your father and I were your age, we’d already been contributing to our families for years. We’ve both worked hard so you could be a carefree girl, but you can’t be a carefree girl forever. You have to think about the future, and your father’s not one for the long view.”

“I know, but—” Her mother’s look made her think better of saying anything else.

Overzealous preparation had ensured that the cabinet under the bathroom sink had been stocked with pink-packaged feminine products since Evelyn had hit double digits. After dry runs orchestrated by her mother, Evelyn felt like an old hand, but when she was cleaned up and her underwear protected, she stood in the bathroom with a sickening fear of the rest of her life. Eventually, she’d have to go into that kitchen and tell her mother, but whatever would come spilling out of her in response would crash over Evelyn in thick, nauseating waves.

She scrutinized her face in the well-lit mirror for signs of this catastrophe, but the sharpness of her features hadn’t changed. Over the last year, the hollows of her cheeks had grown more pronounced and now offered little to counteract the beaklike nose she secretly loved. Her familiar ugliness comforted her, made the relative prettiness of her thick brown hair acceptable. She steeled herself and turned off the light.

Downstairs, the second after words escaped her around half-chewed ham, Evelyn couldn’t recall what she’d said. Her mother’s delight trampled her back inside herself, and she compressed, her smile tight and fixed around meaty goodness she could no longer swallow. Although much of what her mother shrilled had already made the short journey in one ear and out the other, a new subtext in it made Evelyn feel as if she’d just enlisted in something seriously unappealing.

A knobby hand landed on Evelyn’s shoulder, a hand she had inherited in a major way, and her mother’s tone turned accusatory. “You’re not a child anymore, Evelyn, so you need to stop acting like one. You need to consider how other people see you, start fitting in a little more.”

“But—”

“No buts. You’re a woman now, and this is something I know a thing or two about.” Her mother scanned the cabinets and countertops of the kitchen as if gazing over conquered lands. “And you, my dear, have a lot to learn. We’ve indulged you long enough in your whims, the sports and those clothes and . . . and it’s past time for you to understand a few things about how the world works.”

Evelyn had been told by plenty of adults how mature she was for her age. She liked being around her parents’ friends and lurked on the fringes of their dinner parties until she was sent upstairs. A hefty handful of teachers had pulled her aside for praise and projections of a bright future, which, she knew, was going to involve mathematics. Lots of it. Maybe exclusively so. Math was her thing, and it was her father’s thing. So, by the transitive property, it was their thing. Or at least had been. When they sat together over a word problem, it was as adults, as equals. She felt appreciated for something she liked being appreciated for. Though she swam circles in the pool, her trajectory in mathematics had a hell of a slope.

But her prowess with geometric proofs was not what her mother’s admonishment was about. She had been referencing a softer aspect of her mind—one Evelyn doubted existed. She was talking about the parts of the world that lingered outside stopwatches and black and white, right and wrong, true and false, the vast gray area driven by appearances and opinion that Evelyn had never understood. To her mother, adult life was an endless progression of picking sides, a world where getting what you wanted, what she wanted, depended entirely on eliciting the good graces of others.

Now that Evelyn was a woman, her side was picked for her. This side had a dress code and reading list and television preferences. This side had a set of appropriate hobbies, for which swimming qualified only because of its scholarship opportunities. This side had a set of expectations having nothing to do with receiving straight As. Had there been an incinerator in the basement, Evelyn’s favorite clothes—her jeans and collection of swim-team T-shirts—would have burned to a crisp that first night her body betrayed her. As it was, her wardrobe soon became unrecognizable.

Evelyn was mute throughout. Her parents had given her a carefree childhood, one which had left her ill-equipped for rebellion. She was used to pleasing them, even her mother, and had required so little discipline that a mere look could go a long way. Now, her mother’s hand was so heavy with guidance about grace and consideration and endless, stupid patience that Evelyn’s cold terror and confusion had no room to push past those years of easy acquiescence, even though her consent had been to conventions and expectations that had made sense. Doubt crept in around the edges of her adamant disagreement. Her mother hadn’t been unreasonable before—only somewhat relentless—and Evelyn wondered if maybe her mother was right and being a woman was way more complicated than she had anticipated.

Around wardrobe changes and repeated lectures about how to make friends who didn’t reek of chlorine, Evelyn held on to her swimming with a desperate grip. Propelling herself efficiently through a medium 784 times as dense as air—she had looked it up—required an engineering of the entire body that fascinated her. A change of a degree in head position, of a fraction of an inch in the spread of fingers rippled to measurable effect over two-hundred meters. For every adjustment, there were laps of repetition to commit the change to muscle memory until, now, she could escape into a humming blankness in the pool.

*

Evelyn had become exquisitely aware of when she was alone in the house with her father. The hangnail of his proximity invited her worrying attention until it felt red and inflamed. She longed to confess her uncertainty about the path of her life this past year to something besides the thick black line that ran down the middle of her swim lane, but getting her friends to understand was impossible, not with their enthusiasm about her transformation. Makeup smoothed her features into a homogeny almost appealing, and new clothes gave the illusion of a shape that wasn’t there. Her naked bathroom reflection retained its hard familiarity but disappeared under ministrations that had become routine.

A bikini with a padded top was what jerked her out of her somnambulance. Her mother had literally squealed over the jungle-print thing when they were out buying new practice suits for the fall swim season, and now it lay balled up at the foot of Evelyn’s bed. She seethed in the soft summer air about its purchase, about each horrifying step she’d been pushed down this road she hadn’t chosen—the pierced ears and braces, the ballroom dance lessons and Sunday afternoon cooking lessons, the department store makeovers. Nothing in her room brought comfort to her prowling anger, not even her swim medals or the poster of an anonymous butterflier breaking through the water at the start of a stroke—a swimmer so goggle-eyed and swim-capped even gender was buried and irrelevant.

Evelyn sat, trembling with an anger she couldn’t quite direct until her mother ran out to the grocery store and left her and her father holed up at opposite ends of the house. She stomped down the stairs to the den off the kitchen then swayed in indecision outside the closed door, trying to determine the exact knock that would bring a spark of recognition. It started out too timid and ended too forceful. Evelyn thought about running away before he answered, but her feet were stubborn. He was still holding the newspaper open in the dusty quiet when she went in.

“Sorry to bother you,” she said.

“No bother. Did your mother go out?”

“Yeah. She said we were having chicken tonight and that it’ll be ready at six.”

He grunted and made a motion toward his paper.

Evelyn dove in with the last of her nerve. “I don’t understand what’s going on.”

“Oh? Perhaps a little precision might be helpful.”

Evelyn smiled in relief. This was why her father felt solid and real. The act of digging into her own problems to deliver them to him in an acceptable way had always made them instantly manageable.

“It’s about Mom,” Evelyn said.

“Well, I doubt I can be much help with that.”

“But she’s . . . ever since . . . it’s like she thinks I can’t decide anything for myself.”

“Your mother has your best interests in mind, Evie. We both want you to be happy. To have a family someday. If your mother hadn’t known which way was up in these matters, I could have missed all this.” He moved his hands around, indicating nothing in particular. “Her concerns aren’t trivial roots.”

“Yeah, sure, but don’t you think she’s . . . I don’t know. Kind of fanatic? I mean—”

His paper crumpled when he leaned toward her. “You listen to me, Evelyn. As long as you live here, your mother and I are the final word. You may not see her point now, sometimes I don’t, but we have an agreement, one I still believe in. There’s a lot you don’t know about a great many things, most especially yourself. You’ve always been a good girl. Let’s keep it that way.”

“But you don’t know what she’s doing.”

“What makes you so sure of that?” He turned away, shaking out the newsprint. Evelyn stepped back with a feeling of doom so intense she couldn’t bring herself to look at it directly.

Rather than confront her parents with their collusion, she swallowed herself whole and gave in without even internal argument. She wore whatever clothes her mother bought, the lacy bras and cute shoes, and she attempted friendships with girls not involved in swimming. She paid attention to her hair and tried to move with more grace.

At the start of her sophomore year, when her perfectly turned-out self caught the eye of a senior on the boys’ swim team, Evelyn knew this was what her mother wanted. Adam Nutarelli went bare-chested on the pool deck more than he had to, showing off his well-developed body in a jocular, puppy dog way, but his times were nothing spectacular. The flirting began before the team even hit the water that fall. When he caught her alone, his talk was soft and careful. Although Evelyn could see through him, there was just enough substance there that she kept right on looking. But when other people passed them in the weight room or parking lot, he was so completely an ass that she could relax.

He was waiting for her after practice one afternoon, and his smooth talk and lack of regard for her personal space told Evelyn she had two options: reject him without mercy and go home a good girl or accept his advances in a kind of decision that was not her mother’s or her own. Evelyn smiled and took his hand, tasting her resolve like metal.

“Mitchell.” The hiss of her last name jolted her back into full consciousness. Lauren Tate stood puffed up with her hands on her hips. She swam the one-hundred- and two-hundred-meter butterfly, and her motion in the water was so smooth and strong she was pure pleasure to watch.

Evelyn disengaged from Adam and swayed closer to Lauren.

Lauren whispered, “What’re you doing? Adam? You?”

“What do you think I’m doing?”

“Come on, Mitchell. You and Numb Nuts?”

“Hey, didn’t you hear? I’ve changed.”

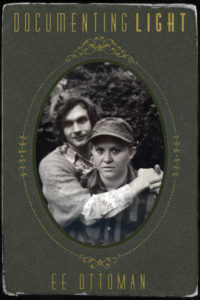

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.