Girling

C. Kubasta

The Driftless Unsolicited Novella Series • Release Date: December 5, 2017

Print ISBN: 978-1-942083-87-0 • Ebook ISBN: 978-1-942083-90-0

Brain Mill Press offers Girling in ebook and in a limited fine first edition printing of signed, numbered paperbacks. Ebook buyers receive access to MOBI (Kindle), EPUB, and PDF files, offered without DRM restrictions. Print book buyers receive a physical copy of the book and access to the ebook files in all formats.

“‘You never told me about that,’ Mom said, ‘but I think a lot of things happened at Mollie’s I didn’t know about…’ and she smiled. Kate thought about the skinny-dipping, but also finding Uncle RJ’s magazines, and kissing Mollie’s brother—the one who got married tonight.”

Girls at home, with their sometimes cruel and sometimes protective families, girls in other girls’ homes, seeing everything. Girls watching boys, girls in the woods, girls in fairy tales, and girls handled roughly, like disposable kittens in a sack for drowning. C. Kubasta imagines all the girls through the lens of two friends hurtling toward womanhood, as they crash into and orbit around men and each other—trying to snatch from life their own terrifying hopes and desires. Girling takes the reader into the magic and secret space that exists in the whispers between two girls, equally best friends and rivals. In direct, engaging prose, Kubasta locates the girl who women forget and men erase in a coming-of-age story that peels away the distortion and hazy memories that protect women from understanding their own power and hubris. This is an engaging fiction debut that exposes the heart and blood of small town BFFs as an unexpectedly sophisticated, fast-paced girlhood rife with fragile innocence, visceral experiences, and self-awareness.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

C. Kubasta writes poetry, fragments, prose and occasional reviews & columns. Her poetry book, All Beautiful & Useless (BlazeVOX, 2015) explored growing up girl in rural Wisconsin; her next poetry collection, Of Covenants, is forthcoming from Whitepoint Press in November 2017. She lives, writes & teaches in Wisconsin, where she is often inspired by the rural, the bodies we inhabit, the subtexts of our relationships & our selves. For each major publication, she celebrates with a new tattoo; someday she hopes to be completely sleeved – her skin a labyrinth of signifiers, utterly opaque. Find her at www.ckubasta.com.

AN EXCERPT from Girling by C. Kubasta

© C. Kubasta, 2017. All rights reserved.

One

The Calico Rule

Kate had never seen a kitten being born. She wasn’t sure she should—that her parents would approve of this new knowledge, this experiential learning. She didn’t even know Sadie was going to have kittens. Usually Sadie cat was outside all the time, unless it was really cold in winter, and then she was only allowed into the house as far as the kitchen. Once Kate and Mollie snuck her up into the bedroom to sleep, but Sadie kept scratching at the door all night, so Mollie opened the window and Sadie went out onto the roof and disappeared.

“Kate!” Mollie yelled, “hurry!”

Kate and Sarah ran to the mud room, and Kate skittered to the floor in front of Sadie’s nest of rags and castoff blankets while Sarah whispered “Shh!” and gave Mollie a stern look. Next to Sadie was a little wet white lump, with an orange spot.

“Is that a kitten?” Kate asked.

“Mm-hmm,” Aunt Sarah answered as she picked up the lump and wiped it down. She wiped it kind of hard and dug around the edges until the lump had a face and stretched open its mouth. She put the lump with the face up by Sadie’s face and Sadie started licking it.

“Here comes another one!” Mollie whisper-yelled, and Kate looked near Sadie’s tail where a trail of slime and another lump seemed to be pushing out. It was another white wet lump, but this one had a big black mark that curved around it. As it was coming out, Sadie stopped licking the first kitten and went still, and her eyes locked onto Kate’s, but not like she was really looking at her. Aunt Sarah cleaned it off, and it joined the other one, rubbing and mewling next to its mother.

There were two more. The third was bigger than the others, but no matter how much Aunt Sarah worked on it, it never started moving. She set it next to Sadie for a minute, but the cat sniffed it and turned away, and Aunt Sarah picked it up and put it in the garbage can on the porch. When she saw Kate watching her, she said, “Stillborn.”

“It happens, Kate. I showed it to Sadie, so she’d know, and then I put it away.”

“Shouldn’t we bury it?”

Aunt Sarah gave her a little hug. “That’s sweet, Katie. But that kitten was never alive. And Sadie’s got a lot of work to do with her three little ones.” The last kitten born was much smaller than the other two. It was three colors, just like Sadie. Mollie said it was the “runt.” She said it would have to work hard to get strong like its brother and sister, but if it could get strong it would be all right. Already the other two kittens were piling over the runt, quicker to Sadie’s belly; even blind, they crawled over it like just another wadded-up piece of cloth.

Aunt Sarah watched Kate watch the kittens. “I’ve got a lot of work to do to make dinner for my own little ones tonight,” she said, “and I don’t think Uncle RJ will have time to make a kitten funeral either.”

She and Mollie had been deep in Mollie’s closet, building a cave of blankets when Uncle RJ knocked at the door. “Girls,” he said, “Sadie’s having kittens . . . ” and Mollie grabbed her hand and they went down to the mudroom. Sadie cat was a calico, curled in the bed of fabric, her fur moving quick, breathing hard. Aunt Sarah had set up a hot lamp over the nest and told the girls to be quiet and watch. After watching for what seemed forever, Kate had wandered back into the kitchen where Aunt Sarah was stirring a big pot of spaghetti sauce for dinner, and the strainer in the sink held elbow macaroni topped with big pats of butter.

“Any kittens yet?” Sarah asked.

“No,” Kate mumbled, “nothing’s happening,” and she picked up the shaker of cheese and shook it to loosen the clumps stuck in the bottom.

“Well,” Sarah said, “it takes some time, but she’s definitely started. Whenever Sadie cat’s ready for kittens she goes to that spot and makes her bed. If you wait a little bit longer, you’ll get to see the kittens being born.”

*

Mollie was Kate’s best friend and cousin, and she lived up on the ridge outside of town. Nearly every weekend Kate would spend a night at Mollie’s, with her Uncle RJ and Aunt Sarah and Mollie’s brothers. The weekend days were wide open—Uncle RJ tinkering in the garage, Aunt Sarah in the kitchen, and the kids somewhere or other in the house or the woods all day until dinnertime. In the summer, they’d walk through the woods to the ridgeline, and over the ridge was a pond. If it was just Kate and Mollie, they’d wiggle out of their clothes and swim—Mollie called it “skinny-dipping”—up where the trees grew thick by the water and they could pretend there was no one around for miles. After, they’d shriek and run back down the path in the woods, clothes sticking to wet skin, pretending to be chased until they got back to the house where they’d warm up in the kitchen while Aunt Sarah cooked a big dinner. She’d make them hot cocoa even in summer, with little marshmallows, and brush the lanks of their wet hair, picking leaves and pine needles from the tangles, sighing, wondering “what they got into,” and laughing as they squirmed. The boys were older and never around, and whenever the girls got near her lap Aunt Sarah would hold them tight, keeping them planted there longer than they could stand. The pots on the stove boiled and steamed and spit.

As Kate grew up, the kitchen at Aunt Sarah and Uncle RJ’s would figure heavily in much of her imagining—in some of her favorite stories, stories that centered around a normal-seeming house fraught with secrets, it was always that kitchen she pictured: the wide-open space in the front room bordered by the long table with extra chairs always ready for visitors; the way the morning light poured in from the back garden; the small area of cupboards that never had enough space to hold everything; the old fireplace they never used, except for the hearth that made the perfect bench for sitting. And there were the side rooms—one full of junk piled high to the ceiling that just might be treasure, one piled with sewing projects that never seemed to get finished, the mudroom always housing Sadie and some litter of kittens.

That trail through the woods became the Ur-trail through the Ur-woods—the woods filled with paths to stay on, paths to stray from. And Uncle RJ, still, was the clearest picture of what a father who loved his daughter looked like—he had so much love it spilled over to his daughter’s friends. After Kate and Mollie were no longer friends, barely cousins, it was Uncle RJ who seemed most sad, who would still call to see how Kate was, and talk on the phone, pretending it was Mollie who wanted to know how she was doing, how school was, if she was liking swimming lessons, if she was excited about her new teacher. The first time her mom handed her the phone, she said, “It’s Mollie,” but it wasn’t. After that, Mom would call her to the phone and mouth “Uncle RJ” and Kate would take the call in the kitchen while her mother cleaned up after dinner, listening with one ear.

*

The night the kittens were born, they ate macaroni and spaghetti sauce with garlicky bread, and Kate kept getting up to check on the kittens and Sadie. All night the little lumps of fur lay curled under the heat lamp in the nest of blankets, the kittens pawed up to Sadie’s belly. Sadie’s purr was loud and deep, and the kittens made little mewling sounds. Kate would reach out to touch one of the kittens nursing, and one of Sadie’s eyes would open and watch her. She hissed once.

Over the next few weeks, whenever she got to Mollie’s, she’d look for the kittens first. They were wobbly and blind, bumping into everything, paws all over each other. The runt got bigger, and soon the only way she could tell it was the runt was because it looked most like Sadie, with orange and brown and black. The white-and-orange kitten was another girl. The white-and-black kitten was a boy and looked like the white-and-black tom that roamed the top of the ridge that Mollie said was Sadie’s boyfriend.

Most calico cats are females. There’s a link between the genes for coloration—especially the orange / non-orange color—and the X chromosome. Even if Aunt Sarah hadn’t known how to sex the kittens, she could have guessed that the runt—three-colored, like Sadie—would have been another girl. Rarely, a male cat has three colors, but they’re usually sickly or sterile, or both. In any case, both Mollie and Kate tried to inspect the kittens to see what Aunt Sarah found when she looked, but couldn’t tell what they were looking for, not on kittens. They didn’t know about the calico rule either, but knew that they both looked like their mothers—everyone said so. Mollie knew how to make dinners already and sew a straight seam; she knew how to tell when her dad was looking for a fight. Kate knew things too, that her mother knew, but didn’t know yet that there would come a time she’d worry that she’d become her mother. That that was something girls inherited from their mothers too—along with the color of their hair, and other things hidden on chromosomes, discovered only lately, under close inspection.

*

Cousin Mollie moved away when they were in fifth grade. Kate thought they’d still see each other—maybe at Christmas—but they were too far away, and the next time was in eighth grade, when Mollie’s older brother got married. But Mollie had new friends and even brought a boyfriend to the wedding as her “date,” and they barely talked or said hello at all. Uncle RJ and Aunt Sarah had gotten divorced, and Kate didn’t really understand if Uncle RJ was still her uncle or if Aunt Sarah was still her aunt. They were both there for their son’s wedding, and they both hugged her and told her how pretty she looked and how she was growing up, but Kate couldn’t remember who was still her family and who she was supposed to love—and who was ex-family and she was only supposed to be polite to.

On the drive home, she was telling her mom about Sadie’s kittens.

“You never told me about that,” Mom said, “but I think a lot of things happened at Mollie’s I didn’t know about . . . ” and she smiled. Kate thought about the skinny-dipping, but also finding Uncle RJ’s magazines, and kissing Mollie’s brother—the one who got married tonight.

There were times when she woke up at Mollie’s and heard angry voices and thought they were Uncle RJ and Aunt Sarah. Once when she nudged Mollie’s shoulder to ask about it, she was already awake. “Just ignore it, stupid,” Mollie said, and she sounded really angry. Kate rolled over to the far edge of the bed and wedged herself between the mattress and the wall. She wanted a pillow to pile on top of her head to drown out the sounds, but Mollie had them all, and they were stuffed around her ears and her face, but what little part of her face was showing was all red and streaky.

Once when she closed the door to the upstairs bathroom, she saw the hole behind the towel where the wall was all crumbly. She asked Mollie about it, and Mollie rolled her eyes at Kate and told her to shut up. After that, she never asked stupid questions, and if she and Mollie came running down the hill and heard Aunt Sarah and Uncle RJ yelling at each other in the garage, they turned and ran back into the woods, pretending they were playing another game until everything became quiet again.

“Mom,” Kate said, “Sadie always had kittens—don’t you remember?”

“Well, I remember RJ taking care of the kittens . . . ” her mom said, and there was an edge to her voice. That’s right, Kate remembered, RJ was her mom’s brother. Uncle RJ was still her uncle.

“Uncle RJ didn’t take care of the kittens,” Kate answered. “Sadie did most of the work, but I only remember Aunt Sarah helping.” Someone should stand up for Aunt Sarah. She would have added, And Mollie, and me, but her mom interrupted.

“That’s not what I meant, Katie. What do you think happened to all those kittens?”

“They went to new homes.” She remembered how after that first time, there were always kittens. Sadie never got “fixed”—that’s what her mom called it, and that black-and-white tomcat was always around. She and Mollie got older and the kittens weren’t so interesting anymore, but there were always kittens, and then the kittens were gone, and Mollie and Aunt Sarah would always say that they went to new homes.

“Their new home was a sack with a few rocks in it, courtesy of your Uncle RJ. He threw them into the pond.”

Kate felt all the breath go out of her lungs. She thought about Uncle RJ, who had spent too much time at the bar at the wedding tonight and, slurring, asked Kate to dance. She was embarrassed, but Aunt Sarah walked up and smiled and took RJ’s arm, and it was almost, for a minute, like they were still married. The way Sarah held his arm was like just before or just after a fight. And the way RJ looked at Sarah anybody could see his eyes were wet, and it didn’t have anything to do with his son getting married.

Kate knew her mother was watching her, even as she pretended to be watching the road. She thought about the skinny-dipping pond, in the quiet of the trees, where she and Mollie thought no one ever came. She thought of their feet ripping open the bags, stepping on the rocks, the little skeletons of rib cages and skulls.

They were waiting at the stop sign to turn onto Main.

“What about Floozy’s puppies?” Floozy was Mollie’s golden retriever, and when she had puppies she took over the garage, behind the table where Uncle RJ kept the drawer of magazines. But Kate couldn’t be there when Floozy had her puppies—no one could. For a week after, if anyone tried to go into that part of the garage, the dog would charge, snarling and barking. After a few weeks, the puppies would venture out themselves, and then Floozy must have decided it was safe.

“Mom, what about the puppies?” But her mom didn’t say anything, just kept craning her neck back and forth, looking for a break in the line of cars.

“It’s always so hard to make this left turn off of Townline,” she said.

*

When Kate first saw the kittens with their eyes open they were bright blue. They started to play and move a little farther away from Sadie, and Sadie didn’t hiss anymore when Kate picked them up.

And then the kittens were gone. Kate went and pet Sadie for a long time, thinking she might be lonely. Sadie purred loudly at the petting, but when Kate tried to pick her up and hold her, she put her claws out and left a big red scratch down Kate’s arm that dripped a little bit of blood. Kate pulled her sleeves down to hide the scratch, and since no one else mentioned the kittens, neither did she.

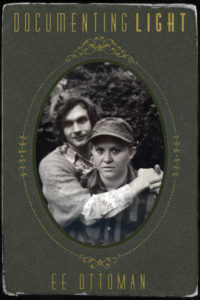

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.